Laughing Gas

Or how a gunmaker saw how miraculous it was, and doctors (stop the presses) didn’t.

Nothing exists

but thoughts.

—Humphry Davy

We all know the one about how Western doctors thought bleeding sick people was a good idea, although some of us might not have realized just how long they believed this (3,000 years) or how recently they stopped believing it (the late 1800s).

Sorry, there’s no punchline there. It’s not really a laughing matter.

But you know what is? Laughing gas.

A wonderful, long article that opens with an anecdote that will make you laugh even without gas came to me via my pal Patrick (thanks!) and it seemed like a good time, in these tense pre-election days, to seek out a few giggles.

So, the thinking was that “bad air” had something to do with the terrible diseases that routinely laid us out—cholera, the Black Death, TB. Made sense, right? Bad-smelling air (especially in Industrial-era Britain) must have had something to do with the diseases that cropped up around it. At the new Pneumatic Institution, set up in 1799 on the theory that if bad air made you sick maybe some as-yet-unmined good air could cure you, a young chemist named Humphrey Davy started poking around with various kinds of gases. He nearly killed himself when he tried inhaling carbon monoxide.

And then—Eureka! Clumsy doses of a newly discovered gas—nitrous oxide—sent him to Cloud Nine. (For hours.) Being a good scientist, he repeated the experiment. During the course of one session, he realized that “nothing exists but thoughts.” Far out, man. He shared the good stuff with—who else?—writers and poets (Coleridge among them), who all enjoyed happy rounds of laughter, singing, and dancing, and undoubtedly penned atrocious poems while under the influence.

Until then, surgeons and dentists did their thing sans anesthetics. Well, there was booze and there were straps to bite on, but generally there was just excruciating pain.

Ask my husband about how much gallstones hurt. (Or ask any of the staff who were on duty the day he went into the ER—they could all hear him holler.) People used to suffer that pain because the surgery to remove it would hurt even more. Ditto with tooth extractions.

Worse than the the days of yore’s honest ignorance about possible anesthetics, though, was the continued times’ willful ignorance. Western surgeons figured pain aided nature somehow and so they’d best just leave it be.

Enter Samuel Colt, a self-taught engineer (apparently, he had more curiosity than doctors did) and the legendary creator of the Colt rifle. This was before that invention, though, because although he had a clever idea, he had no money to develop it. In 1832, he looked around at what was going on in Davy’s lab and saw the potential to make a buck the good old American way: by turning it into a stage show and charging people to see it.

He figured out the science of creating nitrous oxide, which required getting around some chemical realities about oxygen and nitrogen. Each became gas when heated—but they did so at different temperatures. He came up with a method, but it had the potential of exploding in the process, so to safely contain the expanding gas, he devised a silk bag that looked like a bagpipe without the pipes.

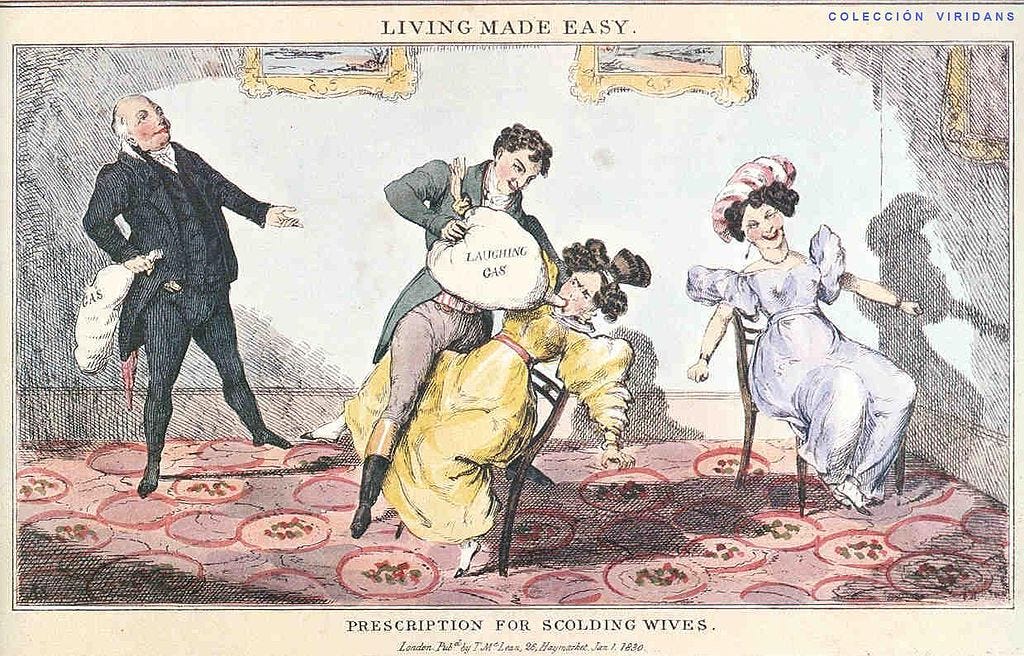

Up on the stage, Samuel Colt, masquerading as a doctor to give it a veneer of respectability, invited volunteers to inhale the gas and do stupid things. (As opposed to the stupid things hypnotized volunteers were doing at the carnival down the road.) Once he collected the funds he needed, he ended his theatre career and went off and invented his rifle.

But before Colt hung up that silk bag, a dentist got to thinking about what he’d seen on that stage. In 1844, Horace Wells did what Davy had done four decades earlier. He experimented on himself while having his wisdom tooth pulled. Then he tried it with 10 patients.

Flush with success, he formally presented it in front of a few esteemed medical men at Massachusetts General Hospital. Despite feeling little pain, at one point his patient gave a yelp—and the doctors rejected Wells and his gas out of hand. They were mean about it, too.

Wells’ life did not end well. He eventually became addicted to the stuff and, in 1848, died by suicide. Here, too, Wells served as something of a Cassandra, a precursor to current concerns about the addictive dangers of laughing gas in recreational use, as well as debates about banning the stuff. (Which has worked so well with alcohol and marijuana.)

But despite his inability to popularize nitrous oxide and his tragic demise, Wells had chipped away at the long-lived notion that pain was a necessary factor in healing. Along came another dentist, who experimented with another promising substance: ether. Its vapor came with its own dangers, too. If you got the dose too high, you poisoned the patient, resulting in breathing and heart problems; too low, your patient would wake up while you were still cutting. (Yikes.)

Meanwhile, Scottish obstetrician John Simpson started exploring the possibilities of chloroform. Oh, my. Happy times. Yes, sometimes his volunteers passed out, and the stuff had the potential to be as dangerous as ether, but women in labor were not complaining.

But you know who were complaining? Doctors, boy howdy, were they ever, loud and clear. This was worse than messing around with nature’s curative; this was breaking God’s decree that women suffer pain while going through labor. They were the ones, after all, who had gotten themselves into this mess. (Agnes Sampson, a midwife, was burned at the stake as a witch in 1591 for using pain alleviators for labor. She was the first woman in Scotland to be dispensed with in this fashion, so perhaps it’s fitting that a fellow Scot should try to address that wrong, albeit nearly three centuries later.)

And then, Queen Victoria—that famously fecund monarch—tumbled onto the stuff. After initial and understandable hesitance during the first handful of pregnancies (chloroform as it was administered then was volatile, after all), she finally gave it a try in 1853 under the very vocal backing of her beloved husband. She was a fan.

Following earlier praise from Emma Darwin (married to that troublemaking truth-teller still haunting community theatre stages and small-town school boards today), Queen Victoria’s was the ultimate recommendation—although even here, doctors and their messaging outlets did their utmost to stifle word of the news:

The Lancet treated the information as mere rumour, advising that ‘the Queen was not rendered insensible by chloroform or any other anaesthetic agent’. This was true as far as it went—Dr. Snow had administered chloroform on a handkerchief and successfully maintained light sedation only.

Still, even with its increased popularity, over the ensuing decades the mixed (sometimes lethal) results of chloroform use sparked people to take a second look at laughing gas.

And thus comes one final character in our story: Edgar Allen Poe’s cousin George.

George Poe invented a canister to safely store nitrous oxide (we use similar ones today), and he patented a respirator for administrating the stuff. Which would lead one to think, Well, now, see? There was at least one not-weird guy in the Poe family tree. One would be wrong. Poe’s overriding goal with his respirator was to use oxygen to bring people back from the dead.

Lagniappe: More an appendix than a true lagniappe, I offer two book titles related to the topics explored here. The Guardian article about laughing gas (on which I leaned heavily for this missive) was excerpted from It’s a Gas: The Magnificent and Elusive Elements that Expand Our World, by Mark Miodownik.

And, for your literary consideration: Joshua Ferris’s second novel, To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, features a dentist who is in the throes of existential angst.

Aren’t we all?