There are no ordinary cats.

—Colette

I know being a cat lady is a cliche. I know cats are common. But there is a reason for their commonality: they are endlessly fascinating.

Even how you feel about them fascinates. Dogs, and many dog people, hate them; so do gardeners and bird lovers. They annoy people who have allergies and folks who treasure their furniture. Some think so little of them that they don’t think of them at all, love or hate. A wildly lucrative Broadway cat musical based on a poem drew record-breaking audiences for approximately 127 years despite the fact that snobs dismissed both the show and its audiences. And a massive number of souls across the globe adore them in art, online, in song, in history, and in life: how they look, how they act, how they exist easily in the world. How can one small, soft creature elicit such varying responses?

Because cats are endlessly fascinating.

I will refrain from whipping out my phone to show you cat pictures plucked from my folders and sub-folders (Wichita Cats; Other People’s Cats; Cats with Corey and Me; Misc Cats). I will not tell you stories about the adorable things Grace and Sprout did yesterday, last week, just now.

But, for this Memorial Day weekend, I will discourse briefly on global cat stories that tell as much about humans as they do felines.

More than a century ago, when we fought that war that was supposed to end all of them, cats helped boost morale for the soldiers festering in those wretched trenches. Historyfacts notes that several types of animals came to the aid of soldiers, including dogs, homing pigeons, foxes, goats, lion cubs, and raccoons, most of them as pets or mascots and some performing actual tasks.

Cats did both: “Though most kitties simply kept their compatriots in good spirits by providing them with loyal companionship, some also used their heightened sense of atmospheric pressure to detect bombs in advance.”

Predictably, WW1 didn’t do away with war after all; it just stretched it out, giving the next war a chance to take a breath before roaring back throughout the world two decades later. In 1948–49, for his acts of bravery on the HMS Amethyst, a cat named Simon won the PDSA Dickin Medal for “disposing of many rats though wounded by a shell blast capable of making a hole over a foot in diameter in a steel plate.” Yes, you read that right: He pounced on rats with his adorable little paws after being hit by a massive steel-busting shell blast. Good on you, Simon.

Rodents on war ships were serious concerns. In addition to eating rations, they gnawed at communications wiring and chewed through ropes—and even planks. As the Ontario SPCA site notes, “As unofficial allies, cats were able to go places that people, or larger animals, could not.” In their “niche job in military barracks and aboard ships,” they could slip into tight spots to stave off the massive damage rodents could do, including spreading disease.

“With their excellent eyesight, cats were also rumored to spot even the faintest of lights on the darkest and stormiest nights. Tiddles, a large black cat, traveled more than 30,000 miles with the British Royal Navy during World War II.”

And back home in war-ridden London, “some families would rely on their cat’s senses to alert them ahead of a bomb being dropped and would retreat for safety to air-raid or bomb shelters.” One gorgeous chap named Bomber “could identify the difference between German aircrafts and planes in the British Air Force.”

(By the way, speaking of German and British planes, I highly recommend an independently published book series by Helena P. Schrader about post-WW2 pilots and shifting powers among the Allies from the point of view of a global cast of characters, including suffering Berliners. I make this recommendation as a person who has no interest whatsoever in war adventure stories and even less in airplanes, particularly small ones, which make me throw up. Just saying.)

Meanwhile, in that other frenemy country we got to know so intimately during the second War, long-ago Japanese sailors believed that calico cats chased away storms and ghosts, and ever since, the cats have been admired in Japan as good luck omens. In early-1600s Tokyo (then Edo) came the creation of the charming maneki-neko figurine, an upright white or gold cat with one arm raised. By the early 1900s, the cats were ubiquitous in Japan, and then they spread to China and into the kitsch shops of the global community.

To Americans, the maneki-neko might seem to be waving hello, but in Japan, raising up one hand and closing its fingers together means “come here”; hence, these are called “beckoning cats.” One theory about how they originated features a samurai that a mystery cat beckoned inside a temple. Shazam! Lightning struck where he’d been standing an instant earlier. Lucky for him. Another theory involves a woman’s cat being decapitated. Its head flew onto a snake about to pounce, saving the woman’s life, so she memorialized her cat with a sculpture. (I’m less fond of that one.)

In an earlier time, both scenarios might have sounded far-fetched, but these days? They make as much sense as most of the stuff we’re fed on a daily basis.

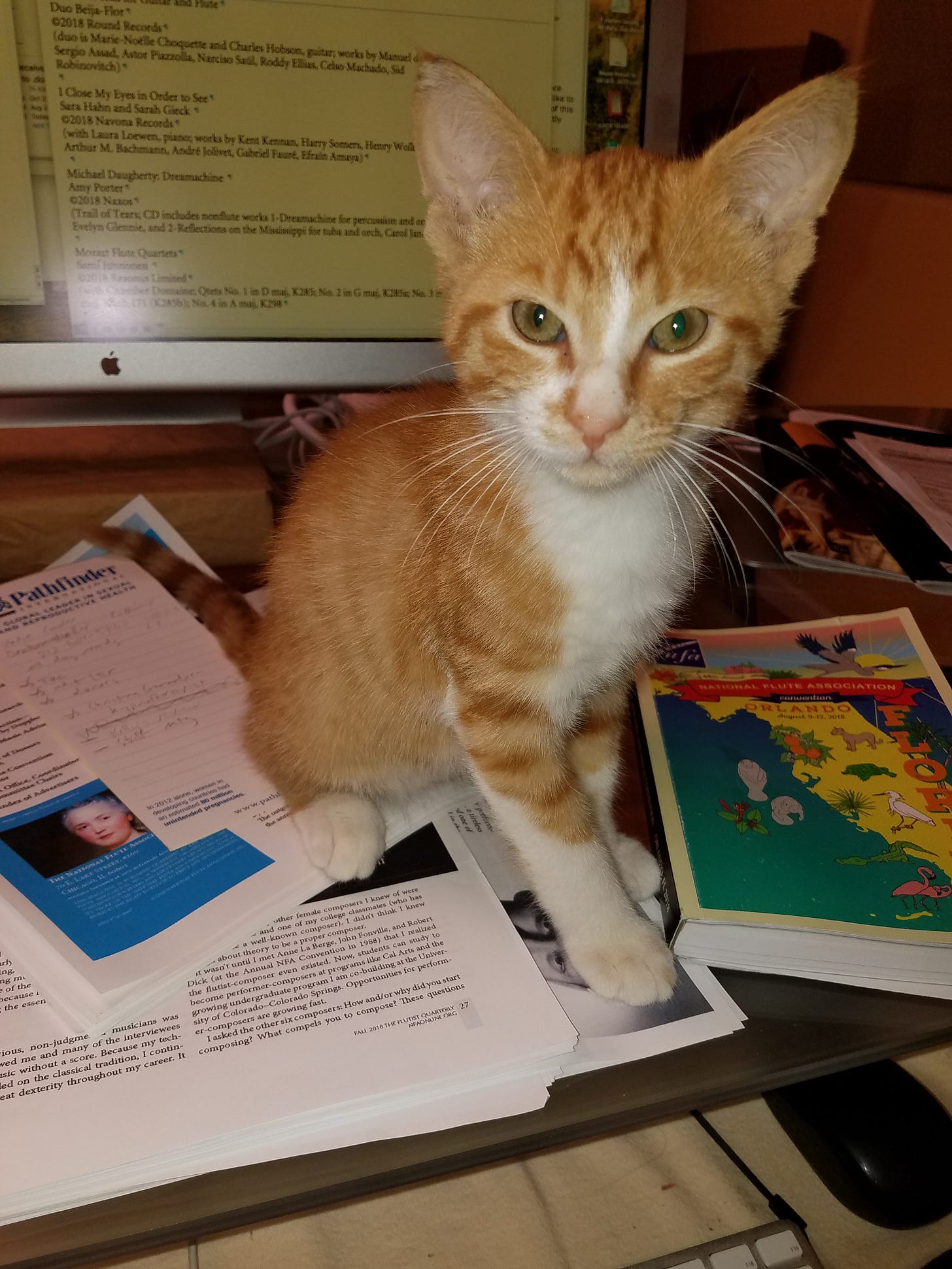

Lagniappe: Speaking of routine lies. I lied to you about sparing you any cat photos. Here’s Sprout when he was wee.

Very apropos, my new cat just came out of hiding. My last one died a couple of months ago, I need feline friendship so I adopted an 8 year old. I feel whole again.

As a fellow cat lover and kitty mom, I thank you for this article, Annie!